RESPONDING TO THE NOW.

For the best viewing experience, we recommend viewing the issue on desktop.

Creative Director

Mia Hancock

Poetry Editors

Emmy Roday

Elizabeth Ruty Shehter

Gillian Egusquiza

Prose Editors

Liel Asulin

Maia Dori

Tamara Rosin

Visual Art Editors

Tamara Rosin

Tania Azaryad

Shock, rage, hope, despair, and most of all, grief. In the wake of the barbaric attacks that took place on October 7 and the ongoing war in Gaza, all of us face the immense task of making sense of this painful new reality.

We watch the news, doom scroll, cry, debate, and try to breathe. We create. We insist on words, on composition, on extracting the tormenting swirl of emotions within and making something tangible from it — a release that can be shared and experienced by others. We write stories and poetry. We paint, take photos, draw, design. In the darkest of days, we insist on creation. We know that to be human is to create, so when it seems as though humans have lost their humanity, we do what we can to restore it. And just as importantly, we share what we create, knowing this is essential to building and rebuilding community, forging understanding, and facilitating healing.

That is what this digital magazine is all about. The artwork and writing in each installation represent people’s raw and real feelings and experiences since the start of the war.

We will be updating the magazine every month, and we are accepting submissions on a rolling basis. Click here for more information on how to submit. We hope you find some connection and healing from reading this magazine.

With love,

The WRITE-HAUS team

Morning Run

Hannah Rosin

The morning air is cold on my throat.

My legs are getting heavy.

My chest is tightening.

I think I’ll walk at the next block.

How far did they have to run?

Would I have made it that far?

How fast did they move?

Could my feet move that fast?

What direction did they go?

Would I have chosen the right way?

How still did they hide?

Could I stay that still?

How exhausted were they?

Would I have given up?

How much pain did they feel?

Would I have been able to bear it?

How did they survive?

Would I have survived?

I go faster instead.

And with fire under my feet

On a quiet street

In a safe neighborhood

Thousands of miles away,

I run for my life

Just to see if I can.

400 Years in the Desert

Holy Era

Chronicle of a relationship in Mexico

Thomas Shore

“Do you want to watch another episode?” I asked.

She is in the bed by my side, curled up into a ball. We haven’t left the room since yesterday. The blinds are down and I have no idea what time it is. All I know is that this was about the tenth episode we’ve watched in a row. Season seven of Game of Thrones. Maybe we’ll get to finish the show before I leave Mexico tomorrow, but something’s wrong. She hasn’t said anything in a while. There’s clearly something on her mind. Maybe she wants to fight. We’ve only fought once before, during a trip to Mexico City, when I didn’t let her take care of me while I was sick. I was feeling feverish and had to sit down and she insisted — almost begged — that I take medicine she had in her bag, but I refused. I dislike taking pills, and I like people doing things for me even less so. Let me be, I told her, I don’t need you to take care of me. She didn’t like that one bit. As we wandered through Chapultepec Park I could hear her boiling like a teapot about to whistle.

I don’t want to talk. I know that whatever conversation she’d want to have will be a serious one and I don’t feel like being serious. I’ll have enough time for that once I get back home. Just don’t talk. Let me hold on to this peace now, while I can. Don’t make this harder than it has to be.

I reach over to check my phone like I always do when I’m nervous, which is another thing I dislike but can’t help. The pull is too strong. The escape from my own thoughts that the endless stream of content grants is as sweet as opium, and ever since the seventh the craving for it has only grown more insatiable. Before, the app used to mostly show me horny-clickbait, luring me to subscribe to some random girl’s only-fans account. Now it’s all about people who hate me. You might think this would be a turn-off, but it only makes me want to scroll even more. I want to be shocked by their hate. I want to be hurt by all the lies they tell. I want to be enraged by their self-righteous ignorance. And at the same time I make a conscious effort to take that kind of content lightly, otherwise I’ll go insane. It’s all a joke anyway. It’s as if, with their mob-fueled anger, they cast me as some Hollywood villain: The evil Israeli child-murderer. What fucking nonsense. I click on the reels tab and the first video comes up. A video of huge crowds of people in an American city calling to globalize the intifada. An interviewer asks some of the protesters what “intifada” means and they don’t know. Ha ha. Then another video of a young girl sitting in front of the camera, saying that all zionists are pigs. Funny. An Egyptian man wearing a keffiyeh explaining calmly that all the horrors of the seventh of October never happened. What a bundle of joy, this little gadget is. Yet I can’t look away. I could’ve gone on much longer but Carolina’s voice tore me away from the screen.

“What does it say?”

“What?”

“You’re checking the news, right?”

“Yeah”

“Anything new?”

“No, not really.”

“So,” she said, “what do you want to do?”

“Nothing.”

“Really? Baby, this is your last day in Mexico. Are you sure you don’t want to do anything in the outside world?”

“No baby, I’m alright just staying here with you,” I say to her.

I gave up on trying to explain the war to Carolina. Not that I tried that hard, but one morning as we were eating breakfast she told me about a story she read on the bombing of a hospital in Gaza.

“I just can’t imagine what it’s like for those poor people,” she said.

“Yes, but–” I said, and was about to continue, but I realized that there was nothing I could say that would’ve made her understand reality as I saw it. She, who has been living her whole life on the other side of the planet and knows nothing of the war I was trapped in my whole life. I tried once to explain the conflict to a Mexican friend. I asked him what he knew of it. ‘Aren’t you killing each other over Jesus or something?’ he asked me. That eliminated most of my motivation. How could I have explained to Carolina about the nature of the cycle of violence I was born into, when all she had to see on TV were pictures of Palestinians being bombed and hospitals being raided?

But did I want her to understand? I never bothered to ask whether she had an opinion. Maybe she did. I didn’t want to know. That was a minefield better left un-trodden, I decided. It was better to push all of that stuff away while I’m with her.

But the last words she said, ‘the outside world,’ came out with a slight laughter that made me wish I could sit her down in a chair and force her to watch Hamas horror footage for an hour. Maybe then she’ll understand that for me, and many others, the world has stopped. We’re living through a day that has been lasting for more than a month now. The date has not changed, It’s still October seventh. But nobody here cares. They all go along with their merry lives as if nothing happened. And I couldn’t care less about anything that happened in their world. At least it’s not as bad here as in other places. From all the videos I watch on Instagram I can’t help but get the sense that those Europeans all fucking hate us. That they want to see us die. They’re all crying for the poor civilians now, but when it was us who were dying they couldn’t stop cheering. All those cultured, refugee-loving Europeans. I wonder how many of my classmates in the exchange program were already cheering on the seventh. There was one girl that posted something pro-Palestinian as news of the massacre broke, who I thought was cool right up until then. We got along well. Thank god I haven’t seen her since, I wouldn’t have been able to stand the sight of her. All of them, a bunch of fucking—

“Okay,” she said, “then put on the next episode.”

“Great,” I answered, “one more and we’re done with season seven.”

I feel as if I’ve known Carolina for much longer than I actually do. It’s almost bizarre to think how accidental our meeting was. We both attended a friend’s birthday party. People were dancing salsa: a dance that I only know the most basic moves of. I was alone, so was she, and I just came over and took her by the hand over to the dance floor.

We only exchanged about five sentences beforehand, yet some force compelled me to move as if my feet were on rails. We had been spending time together ever since and after the seventh, when I retreated to this little sanctuary away from the word, she joined me. The only person that I cared for in this foreign land. We would cook for each other, watch television and have sex, all things that we enjoyed doing together. I was satisfied to be stuck there together, rotting away in a dark little room. And when I managed to push everything out of my mind and pretend that nothing bad ever happened, I was happy.

When I told her I was called to serve in the reserves it brought her to tears. Her voice became hoarse as she begged me not to leave her, said that I shouldn’t go and fight, but I told her that I had to. She didn’t say anything but continued to plead with her eyes. “Don’t go,” she would sometimes say out of the blue. And the more she said it, the more I thought that maybe I really shouldn’t go. Maybe I’ll just wash my phone down the toilet and allow her to take care of me, and we’ll stay like this for a year, or forever.

She is peaceful now, wearing her pink pajamas and her black hair loose, her big brown eyes staring at the screen. My morose mood seemed to have swept over her. I pull her close to me, One hand on her stomach and the fingers of the other slowly tracing over the soft skin of her breast.

“What are you doing baby?” she whispers. I inhale the light, coconut scent of her hair like it’s the last bit of oxygen on earth as I slide my hand down toward her crotch.

“Do you want me to stop?” I whisper back.

She begins to quiver and her breath grows heavy. “No.”

I slide out of my underwear and yank her pink pajama pants down. She wiggles out of them and I pull her hips closer to mine. She turns her head to kiss me as I enter her and for a few minutes there really is nothing in the world — in the whole universe even — but her, until we both are done and separate.

After a moment of rest she gets off the bed and goes over to the bathroom.

The front page of Ynet has a new cover story: The testimonies of the sexual assault on the seventh. When did I pick up my phone again? It just appeared in my hand. Swallowed me whole before I noticed. I skim through words, lightly tapping my screen, until my eyes halt upon a passage. ‘I was hiding in the bushes for some time when I saw them bring a young girl. There were five or six of them. They started to—”

“Let’s keep going,” Carolina says, sitting back down on the bed beside me.

“Baby, I’m not sure I can… oh, you meant the TV.”

She gives me a curious look. “Is something wrong?”

“No. Why do you ask?”

“I don’t know. you look a little angry.”

I smile. “Everything is fine, don’t worry baby.”

The phone is still in my hand. I wait for Carolina to be distracted by the TV and go back to reading. I read paragraph after excruciating paragraph.

“Oh my god!” Carolina exhales, “I can’t believe Daenerys just did that! did you see?”

“Yes, it’s crazy.”

I’m done reading the article. King’s landing is on fire. I put my phone away and the only question that is left on my mind is, what am I supposed to do with the knowledge that I live in a world that is so evil? The world has never been so dark.

It is night and we are laying in bed together, falling asleep. My left arm is under her neck and she is curled up into a ball on the other side of the bed like she was earlier. I try to pull her close to spoon her but she resists, so I give up and lay on my back.

“Is this it?” she asks me without turning to face me. “After you go back, it’s over?”

“Yes,” I answer, and it feels like pulling the pin on a grenade.

She gets quiet for a while until she says, “Why did you take my hand that day, at the party?”

“Because I wanted to,” I answer.

She doesn’t talk for a while. I lift myself up to see her face thinking something might be wrong just as a tear rolls down her eye.

“Next time,” she replies, “please, don’t do it. Next time you leave me alone.”

Why did I do it? Why did I take her hand that day at the party and took her to dance? Probably because I thought I had nothing to lose. And yet, I’ve lost something. Once I leave, I’ll be less than what I was before I met her.

“Okay, baby.” I say, “as you wish.”

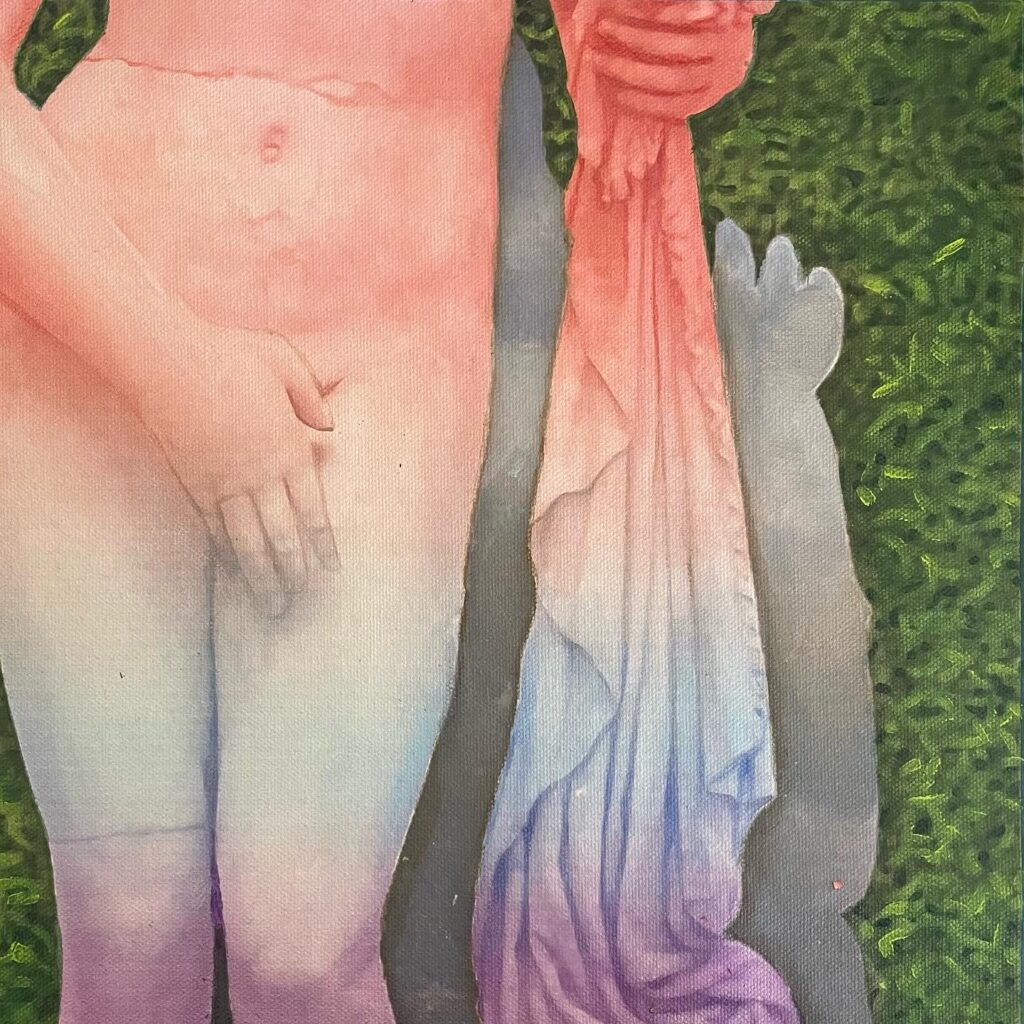

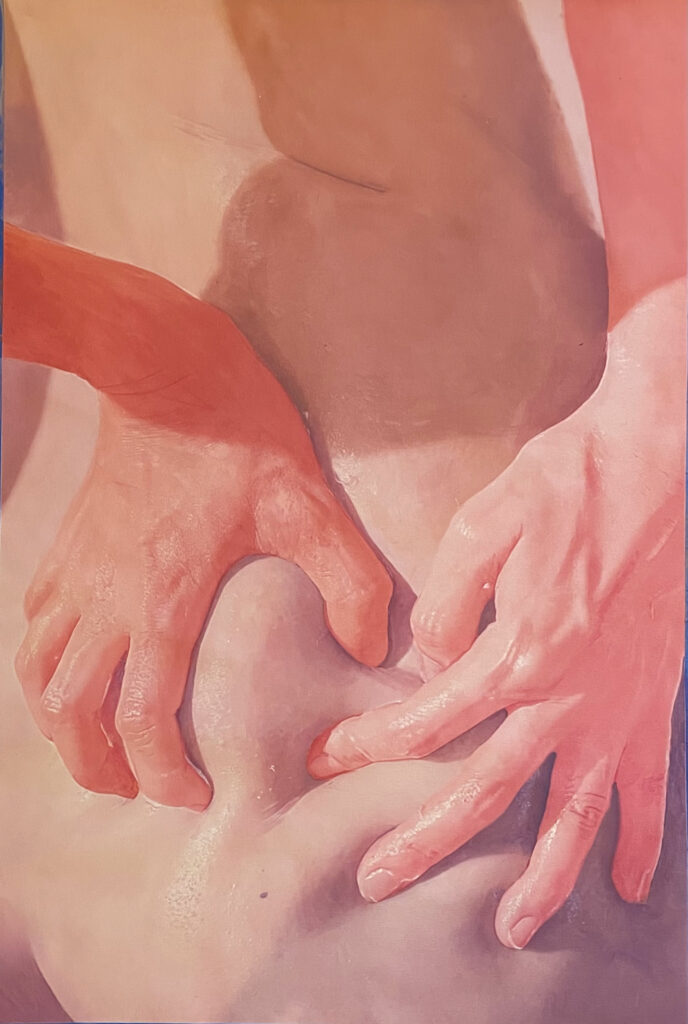

Within the Flesh

Elsa Ers Brosh

Withing the Flesh

Elsa Ers Brosh

s

p

i

r

a

l

i

n

g

Michelle Chiera

I hate the sound of airplanes

You ever have one of those dreams where you can’t move

to the point where it feels like someone’s pinning you down and you scream but no sound comes out and you can’t

wake up and worry

maybe you are screaming out loud and your neighbors have a separate group chat to talk to shit about you and you’re known

as ‘the screamer’

or ‘the banshee,’

or there’s some childhood lore about you living in the haunted apartment which it kind of is anyway

since the winds changed

and the evil crawled out of the shadows in broad daylight and you start to

think maybe that scene in the Prince of Egypt

—aka the Bible— is actually true and spirits are real

and maybe

the Bible is real

and if it is it’s kinda wild you just referred to it as the Prince of Egypt

which is similar to referring to the Odyssey as, I don’t know, Aqua Man, and all of a sudden

you’re watching old episodes of the Real World and you’re crying

because they just told a kid his mom died on Valentine’s Day

on TV and now you’re sad that this memory is now forever recorded,

and it’s unbelievable but you’re also deeply sad

for this person you never met but you kind of feel like you could have so you have this pit,

this avocado seed pit in your stomach

but you can’t even sit with it because it’s so uncomfortable and sad and scary

but then you notice he’s wearing a live strong bracelet which is kind of a hysterically ironic statement on us, the ‘performative generation’ because like why were we letting a drug using bicyclist sell us mass and unethically produced silicon bands that were probably most definitely polluting sacred rivers somewhere

for like,

(what was it even?)

I think pancreatic cancer but then it turned out he got ball cancer (respectfully) from the drugs he took to ride a bike and we all felt bad for him

because he represented the American spirit and it’s all just so funny and ironic and sad

but maybe it did end up saving (curing? Whatever, he didn’t) pancreatic cancer and then probably more dudes got tested for pancreatic cancer and, who knows, maybe even brought steroid use down, or up…

does it matter? this guy rides a bike for a living

and, in reality, who is it hurting? until it is hurting someone

or several someones

Even if the people who are weirdly hurt by it always had their own suspicions

Or intuition

that something was going on, or going to happen I always have that feeling

that feeling that they talk about

where you’re sure you’re going to die

where you suddenly have total clarity

and your life starts flashing before you in glossy Polaroids

even the parts you didn’t experience

with the people you don’t even know or with memories you haven’t made yet and it’s all because this kids mom died on national television.

I hate the sound of thunder.

Why do we say ‘I’m thinking of you’

because you’re not

Not in a real way at least, because

if you were really thinking of them it would consume you and you wouldn’t be able to move you’d become one of those What’s Eating Gilbert Grape moms who become so attached to the couch they’re basically half foam pillows or whatever the fuck a couch is made of

to the point where you can’t even think of this person as being a person your age with dreams and hopes and wants and insecurities because surely she can’t be like you and I can’t be like her because that means we can all become that, and that is terrifying

because of all the things I can’t say

or at least say out loud because we can’t say them out loud or at least not in English because language now just feels like one big trauma bond as people move from one place to another trying to forget and forget to remember and remember to forget all the things too terrible to say at least in your native language because somehow that’s still the clean part of you until it’s not.

I hate the crack of lightning.

Do terrorists carry umbrellas?

No, right?

I like to think not, at least as a part of my danger assessment

when I see someone walking towards me.

Specifically when they walk towards me.

I hate them

I hate that I think of them

I fear them

I fear myself

I fear hate

We did this

They did this

I feel nothing

Oh the irony.

I feel for them

I break for them

I cry for them

I cry because of them

I cry.

The Embrace

Elsa Ers Brosh

Window of Tailor’s Shop, Jerusalem

Rick Blumsack

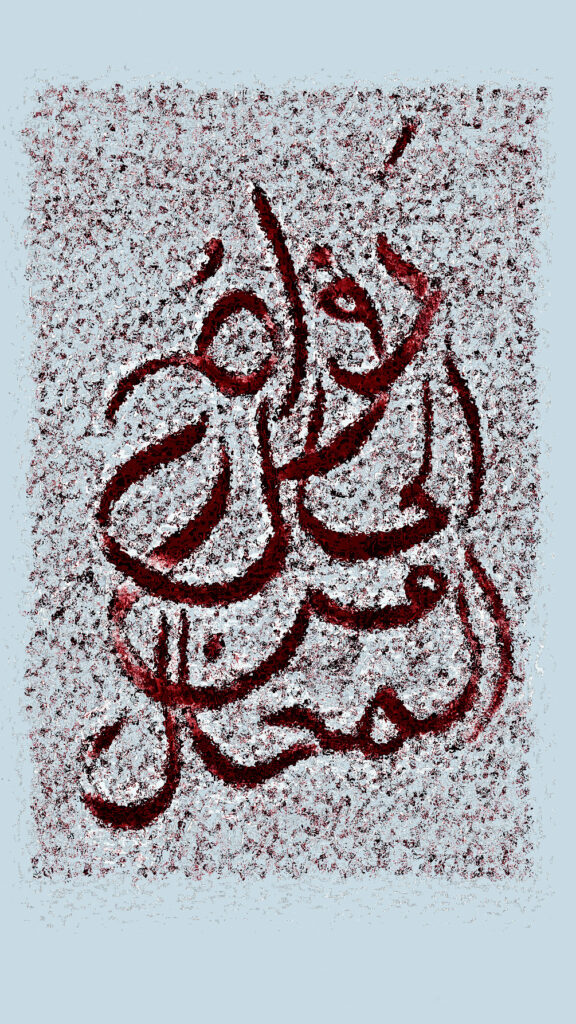

To any god there is

Uri Ofer

I turn to any god there is.

If Allah,

then Allah;

Please keep in every person

a hint of childhood

לכל אלוהים שיש

אורי עופר

אני פונה לכל אלוהים שיש.

אם יהיה זה אללה,

אז אללה;

שתשאיר בכל אדם

נימת ילדוּת

The Inscription

Gabriela Paloa

(based on a true event)

In the weeks after, Esther would run those details through her mind on an endless loop; how she’d prepared one pot of ratatouille with coriander and a smaller pot without for Ron and Anna, who found the taste of coriander abhorrent. She would remember how tedious it had felt to chop up nearly a kilo of tomatoes for the meatball sauce, instead of simply emptying a tin of skinned tomatoes into the pot, because Anna and Tom claimed they could tell the difference. She remembered how she’d reached for her phone and snapped two photos of the casserole packed full of shiny red and orange stuffed peppers, before slipping the dish into the oven on the tray below the roasting potatoes. A perfect candidate for a cookbook, she’d thought with secret pride. She also recalled the underlying resentment she’d felt that Friday morning, when she was anxious to put the finishing touches on her presentation for the Rotterdam conference on ‘The role of dialogue in conflict zones’ the following week. How wrong she’d been about everything.

As always Esther had prepared far too much food. It was just the five of them and Ben, one of Ron’s work colleagues, who was staying over whilst his wife and children were away in Crete. There’d be plenty of left-overs for the next day.

The sirens and the sound of rocket fire started early the following morning just as

Ron was tying up the laces on his new trainers. Esther and her family were used to the drill and they all rushed downstairs to the safe room. Tom and Guy dove onto the mattresses strewn on the floor. Esther, Ron and Ben sat on the floor cushions, and Anna snuggled up to her father with her head in his lap. They all waited for things to stop and to go back up to bed. But this time it wasn’t just ten minutes or even half an hour, the rockets and sirens sounded relentlessly, on and on and on. After a while Ron tried to catch Esther’s eye, but she shook her head very slightly and put her hand on his arm, as if to say, I know what you’re thinking but just try to keep calm, we don’t want to worry the children.

After what felt like a long time the rocket fire became more sporadic, but in the intervals between the barrages the family could hear the roar of motorcycles engines, gunfire and shouting close by. Tom and Guy huddled up to Esther. She sat holding their hands, but her eyes were darting from side to side as if she was trying to listen with her eyes as well as her ears. Ben sat hunched over his phone, exchanging text messages with his wife in Chania. It was clear to all, this was an entirely new situation.

When they heard the front door being forced open upstairs, Anna gasped and Ron darted silently to pick up the only stool in the room and jam one of its metal legs between the door-handle and

the door-post, effectively locking the safe-room door from the inside. They could hear a cacophony of shouting and shoving, the thud of heavy boots through the ceiling from the floor directly above, the opening and slamming of doors, the sound of chairs being dragged, the clang of objects being placed heavily or dropped and the jarring sound of scratching cutlery.

Esther held the boys close, breathing deeply and soundlessly, her eyes were wide open, she hardly dared blink. No-one was mouthing messages to each other anymore. Ben stopped texting and put the phone down to the side. Surely help would arrive from the neighbours or from the police or defense forces, thought Esther. But nothing of the sort did arrive. It was clear to each of them that staying still and silent was essential. And that is how they remained, a frozen huddle of adults and children. It seemed to Esther as if the world was holding its breath, as if the very passage of time was stalling.

Hours passed.

Finally it became clear the sounds from upstairs had ceased and the intruders had left. Similarly even the noises around the house had fallen silent. Ben’s phone had run out of battery and no-one else had brought their phone down in the morning, so there was no way of contacting the neighbours to find out what was going on. Esther said they

should wait a while longer before opening the room door and going up stairs. When Esther and her family emerged from the safe room they found the kitchen chairs thrown on their backs. There were knives and forks strewn on the floor, the salt-cellar and three broken plates. The fridge door was swung open. All the bowls and pots of food from the night before were on the kitchen table but completely empty; the large metal meatball pot and the casserole dish with the stuffed peppers, the roasted potatoes, the green beans in lemon sauce, the beetroot and cumin dish, the cucumber and yogurt salad, the tomato and basil salad, the vegetarian moussaka, both the ratatouilles and the chocolate mousse. Every scrap of food had been devoured.

It was Guy, the youngest of the three children, who first noticed the sign on the wall above the sink. The intruders had taken the grey marker from the top drawer and drawn a haphazard heart-shape. Inside the heart was a short inscription. Ron looked at Ben, who was a fluent Arab speaker. Ben swallowed hard.

‘It says,’ Ben said, ‘the food was tasty so we decided not to kill you.’

When, two days later, Esther found the photos she’d taken of the stuffed peppers on her phone, it gave her a jolt. She deleted them immediately.

Layers of The Unseen 01, Photograph

Mona Haj

Layers of The Unseen 02, Photograph

Mona Haj

poem #48

Blossom Hibbert

Our sky only beautiful when it is dangerous in

copper torrents my feet tread intimately with

nonsense often intrigued by those bright green

eyes on top of His

lit cigarette under drizzling rain of streetish

atmosphere & can you hear? Wet foxes making love

whilst Our people sit in their dark living rooms

knitting shiva into a fleece of rags?

By the fireplace? You can’t hear it? Whilst the

hostages cross an Egyptian border to

safety, I can hear it

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Leenoy Margalit

My baby cousin (who is no longer a baby but an 11 year old boy I once held in my arms) takes my hand in his and leads me behind the house to the backyard that has become a farm. As he feeds the four goats and two sheep and one dog and twelve ducklings, he teaches me that the Hebrew word for pomegranate is the same word for hand grenade. We talk about paper airplanes and remote controlled cars and war but not about school. We pick and eat figs off the tree my mother climbed as a child, and he laughs when I confuse the words shrapnel and eyelashes. He tells me that each time the sirens end, he runs to the field behind the farm to collect the rocket fragments scattered between grass blades. When he shows me, he holds each piece of metal in his palm like a prize you bring the class for show and tell. He asks me how big our bomb shelter is in America. He tells me he is not scared. Not like his sisters who still sleep in their mom’s bed and take short showers. He knows exactly what to do by now. We walk back towards the house carrying fruit in our shirts, my hand still in his. A year from now, I will be somewhere in America where we do not have bomb shelters and my baby cousin will be here. And he will still pick figs and feed the goats and the sheep and the dog that ate the ducklings. He will talk about paper airplanes and remote controlled cars and war. At the same time, someone else picks eyelashes off of an 11 year old boy who is not my baby cousin. And later we will hear about the pomegranate that burst open. How the red stained everything for days.

Pain is familiar here

Maayan Agmon

Yet again I am faced with my cowardness. Although I’m not so sure it’s that anymore; it feels more like paralysis. A strong urge to shut down. A grand tiredness that causes unsettling thoughts. Sometimes my iPhone memories show pictures from the trip in India, and it seems as if these are the only moments my heart gets a break. Yesterday I remembered the mountain. 3,500 m. 3,800 m. 4,000 m. 4,200 m. These are no longer heights upon which to walk or breathe, these are heights where you go up and go on because soon you will start going down. You can go back, but not really: it will take two days. Again, the thought creeps in, but it will already take three, four, five days – so you go on. And it’s beautiful. So beautiful. There is no beauty like that. You see, this beauty is engraved in my mind, it gives me a moment to smile within the inferno. Even though there wasn’t enough air. Somehow there is. But still, you go to sleep early, you walk slowly, and you take many breaks.

My dad thinks I should pursue a career in politics. That there is room for my voice. My mom advises me to go abroad for a while and see how human rights organizations work there, get some air and perspective. Sometimes people ask me, “Wait, don’t you work at that place with the Palestinians?” They say they imagine it must be really hard now, and ask what we do with the kids there, and how do we explain it to them? And I do work at that place with the Palestinians, but now I don’t know if I’m allowed to talk about it or not. And I’m not that convinced that there is room for my voice. And if there is, I still haven’t learned how to demand that room. Frankly, if I had a voice, it would have made things easier, but right now all I have is a body, and it’s tired and hurting and in disbelief. The body slices into itself. Its frustrated screams quietly diffuse into its own cells, adding stone after stone on the pancreas, liver, lungs, spleen, kidneys.

Here, in the silence, I might know only a little, but I know what pain is, and it feels like a lot. Other people speak and for a second I feel like I find myself, but not really. How do you explain what Ahavat-Hinam1 is? How do you describe God, and why does each person hear her speak differently?

The streets are talking, commemorating, and fighting, using spray paint and brushes. For a moment there I think maybe I will also speak among them. Yet again I am faced with my cowardness. Although I’m not so sure it’s that anymore, perhaps obedience. A belief in law and order. A sense of respect to the surrounding. This respect is what asks me to pick up the old snack wrapper from the street and put it into the garbage. It is the image of the young scout. The ambulance First Responder. The lonely person who is not afraid. But fear is important. In the summer, in Europe, I told my friends about the situation here2. About how this year during a protest someone tried to run my brother and I over. About how this year during a protest the cops rolled people down the grassy slope of the highway bridge. About how this year during a protest a white car stopped and from it came a driver wearing short pants, a Tassel tank top3 and a knife. Where is my fear? Where are my legs? How are they still walking? How can they still protest?

I am chasing Pandora, asking her to reopen the box. There, we both unleashed hope and it’s now in the air, somewhere 4,200 m high. Here in Israel we don’t have heights like that.

There are horrors they will not understand. There are horrors we will not understand. I have no way to hold all of this suffering. I can hug the person in front of me. What else can I say but “I love”? People are people are people are people. What are you thinking about before you fall asleep? I am not thinking, it is only the wine that makes me feel slightly fine.

1 Ahavat-Hinam in a free translation is simply “free love”, however it is a phrase taken from rabbis such as Rabbi Yehezkel from Kuzmir and Rabbi Isaac Kook. It is a phrase that came as a contrast to free hate, claiming that the only thing that can face hate is love. The only thing that can stand in front of destruction and bring about the building of something new is free love.

2 Before the 7th of October was a year with weekly protests against the government and for democracy

3 A Tassel tank top is a Jewish religious garment for men

ושוב אני ניצבת בפני הפחדנות שלי. למרות שאני לא בטוחה שזאת פחדנות כבר, יותר מרגיש כמו שיתוק. רצון עז להיכבות. תשישות גדולה שגורמת למחשבות מערערות. לפעמים בזיכרונות של האייפון קופצות לי תמונות מהטיול בהודו ונראה שאלה הרגעים הבודדים שהלב שלי מקבל רגיעה. אתמול נזכרתי בהר. 3,500 מטר. 3,800 מטר. 4,000 מטר. 4,200 מטר. זה כבר לא גבהים ללכת או לנשום בהם, זה גבהים שעולים וממשיכים, יודעים שתכף תתחיל הירידה למטה. אפשר לחזור אחורה אבל לא באמת, זה ייקח יומיים. שוב המחשבה מזדחלת, אבל הפעם כבר ייקח שלושה, ארבעה, חמישה- אז ממשיכים. ויפה. כל כך יפה. אין יפה כזה. הנה, היפה הזה חרוט לי בראש, היפה הזה נותן לי רגע לחייך בתוך התופת. אפילו שלא היה אוויר. איכשהו יש. אבל עדיין; הולכים לישון מוקדם, והולכים לאט ועושים הרבה הפסקות.

אבא שלי חושב שאני יכולה וחייבת להיות בפוליטיקה. שלקול שלי יש מקום. אמא שלי ממליצה לי ללכת לחו״ל קצת ולראות איך ארגוני זכויות אדם עובדים שם, לקבל קצת אוויר ופרספקטיבה. מדי פעם שואלים אותי ״תגידי, את לא עובדת במקום הזה עם הפלסטינים?״ וחושבים שבטח זה נורא קשה עכשיו ומה אנחנו עושים שם עם הילדים ואיך אנחנו מסבירים. ואני באמת עובדת במקום הזה עם הפלסטינים אבל אני כבר לא יודעת אם מותר לספר על זה או לא. ואני לא כל כך משוכנעת שלקול שלי יש מקום. ואם יש, אני עוד לא למדתי איך לדרוש את המקום הזה. האמת, אם היה לי קול זה היה מקל על העניינים, אבל כרגע יש לי רק גוף. והוא עייף וכואב ולא מבין ולא מאמין. הוא מפלח בתוכנו, בתוכי ובתוכו, את הצעקות המתוסכלות שלו, מכניס אותן לתאים בלחש, מעמיס על הלבלב והכבד והריאות והטחול והכליות- אבנים.

כאן, בדממה, אני אמנם יודעת מעט, אבל יודעת כאב, וזה מרגיש כמו הרבה. אנשים אחרים מדברים ולרגע אני מרגישה שאני מוצאת את עצמי, אבל גם זה לא באמת. איך להסביר מה זה אהבת חינם, איך מתארים את אלוהים, ואיך זה שכל אחד שומע אותה מדברת אחרת?

הרחובות מדברים, מנציחים ורבים בעזרת ספריי ומכחול, ולרגע אני חושבת שאולי גם אני אדבר בתוכם. שוב אני ניצבת בפני הפחדנות שלי. למרות שאני לא בטוחה שזאת פחדנות, אולי ציות. אמונה בחוק ובסדר. כבוד למרחב. הכבוד הזה הוא שמבקש ממני לאסוף עטיפת חטיף מהרצפה ולשים בפח. זה הדמות של השומרת הצעירה. המע״רית. הבודדה שלא מפחדת. אבל הפחד הוא חשוב. בקיץ באירופה סיפרתי לחברים על המצב פה. על איך שהשנה בזמן הפגנה ניסו לדרוס אותי ואת אח שלי. על איך שהשנה בזמן הפגנה השוטרים גלגלו אנשים למטה מהדשא מתחת ליציאת איילון שדרות רוקח. על איך שהשנה בזמן הפגנה מכונית לבנה עצרה ומתוכה יצא הנהג עם מכנס קצר, גופיית ציצית וסכין. איפה הפחד שלי? איפה הרגליים שלי? איך זה שהן עדיין הולכות? עדיין מוחות?

אני רודפת אחרי פנדורה, מבקשת שתפתח שוב את התיבה. הנה, יחד הוצאנו את התקווה והיא באוויר, איפשהו בגובה 4,200 מטר. פה בארץ אין לנו כאלה גבהים.

יש זוועות שהם לא יבינו. יש גם זוועות שאנחנו לא נבין. אין לי איך להחזיק את כל הסבל. יש לי איך לחבק את האדם שמולי. מה עוד אגיד חוץ מ-״אני אוהבת״? אנשים הם אנשים הם אנשים הם אנשים. על מה את חושבת לפני שאת נרדמת? אני לא חושבת, זה רק היין שעושה קצת נעים.

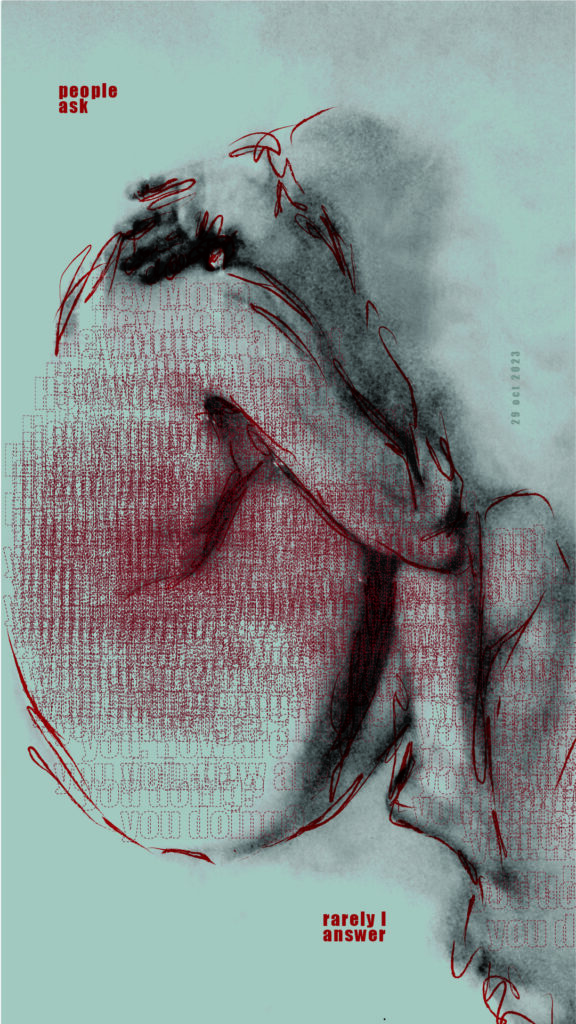

Untitled

Photograph by Diana Dawahdi Shalash

Artwork by Mona Haj

It Shall Pass, Ballpoint Pen Drawing edited Digitally

Mona Haj

Detail 01, Photograph

Ronit Holtz

MEDITATION

And for a moment, I want

only my pain to feel. To break

the connection that binds us

by breath and heartbeat.

I ask: Where does my pain end

and yours begin? Where to untangle the end of me

and the start of you? Where to mark

these boundaries of separation?

The mute voice of wisdom whispers: Silly human!

You silly little human.

I grit my teeth. I breathe. I feel my heartbeat.

I breathe. I feel my heartbeat.

I breathe. I feel your heartbeat.

I ask: Where do my love and your love meet?

Where to tangle the ends of me and the starts of you?

Where to heal, where to heal?

Where to hold so I am you and you are me?

U

H

E

S

s

C

N

S

SUCHNESS

Lior Maayan

We were not born to be good,

we were destined to survive

A box of genes in the world

Formed the self

And self created God

And God saw good

and like in a movie that is shown backward from the end to the beginning

All the good we are

Is in spite,

Not because.

Bring Them Back, Paper Collage/Digital

Aida Bechar

SPILLED MILK

Leeor Margalit

Dedicated to Dudy Laniado: a dairy farmer who, after hearing of the terror attacks on Kibbutz Nir Oz, risked heavy fire to milk and feed the cows.

Suddenly, you wake up and you mourn the little girl you just met in your dreams.

Suddenly you put down the dish you were washing and ask yourself,

“Who will milk the cows tomorrow morning?”

You are aware that there’s an ongoing hostage situation but –

who will feed the cats?

And you know that people have been slaughtered, you do

but suddenly, while driving to the grocery store, you pull off to the side of the road and you

wonder what will happen to the fruit ripening in the fields, no one there to harvest it, left alone to

fall into the bloodstained earth and rot.

And who will milk the cows tomorrow morning?

They Soon Will Become Angels, Oil on Canvas

Moriya Kaplan

Yarden Roman, Digital Illustration

Didi Kfir

Things That Words Cannot Describe,

Digital Illustration

Didi Kfir

A WORD

NO ONE

REMEMBERS

Bruce Black

I live thousands of miles

away from the war

yet the bombs that fall

shatter the peace here

the same way they shatter

the buildings in Gaza.

And though I don’t watch

the images on TV of

the crumbled concrete

blocks or the bodies

of the dead dragged

out of the rubble,

I weep for the lives lost,

especially for the children.

Each day the war goes on

and more people are killed

and more people die and

there’s more destruction,

each day is another lost

opportunity to seek peace,

to end the madness.

And here I sit at my desk

thousands of miles away

praying for the hostages

held captive for weeks—

not knowing if they’re still alive,

if they’re being fed and cared for,

not knowing if they’ll be released safely.

I don’t know anything except

that I wish for their safe return

and pray for an end to the killing

and long for peace—a word

no one remembers.

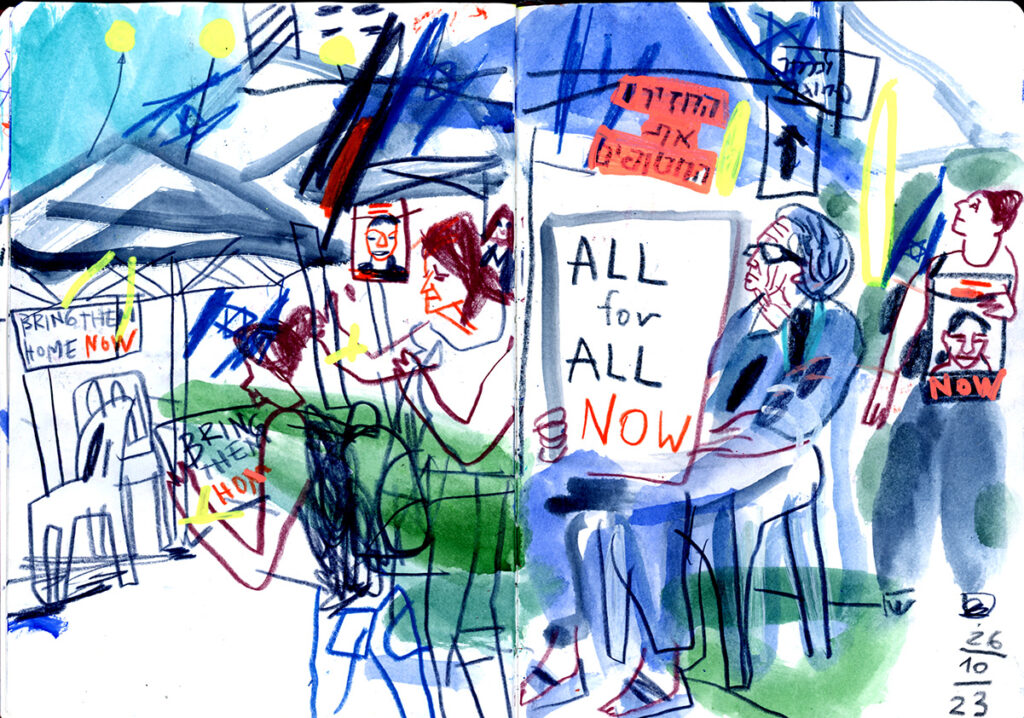

Freedom Rally, Watercolor and Acrylic in sketchbook

Marina Grechanik

Freedom Rally, Watercolor and Acrylic in sketchbook

Marina Grechanik

even our tears will fill the trunk of a tree

Sarina Shohet

The planet is healing

and like all fevers before

they break, it rises from

core to mantle where

picture frames line a mass ofrenda

populating every day with enemies.

Murder means nothing to the soil that

it feeds.

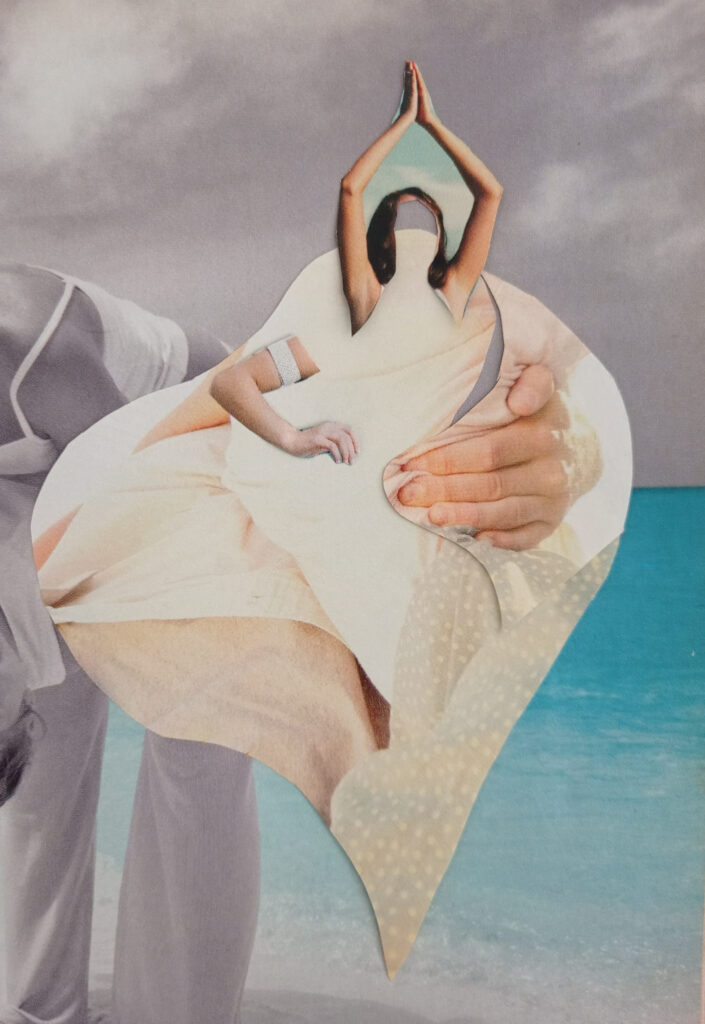

Bring Me Back, Paper Collage

Aida Bechar

Freedom Now Rally, Watercolor and colored pencils in sketchbook

Marina Grechanik

Bring Them Home 1, Acrylic Markers in Sketchbook

Marina Grechanik

After October 7th

Abby Yucht

we were all dead and moving

as if electrocuted

a nation of frankensteins

forced to bring bodies back to life

and with electricity searing

through our veins- electric fence fallen to a puddle-

we began to pray for rain.

please, oh God, rain

to clear blood from roofless homes, rockets

to turn to rain around innocents-

Abraham prayed for the lives of rapists and God said no,

anger rained down on Sodom.

now the rain tastes so salty

of the dust clearing before our eyes,

landing on our speechless,

deadened tongues,

these are tears,

living, human tears and

the rain is shaking

with the shake of an electric nation.

the rain tastes salty.

the dust will clear.

CONTRIBUTORS

Abby Yucht

Abby Yucht is an emerging poet living in Jerusalem, Israel. Born and raised in Teaneck, NJ, she immigrated to Israel with her parents and siblings in 2015. She received her BA in psychology and musicology from Bar Ilan University and is starting an MSW at Hebrew University. Abby works in the field of mental health rehabilitation by day and loves to run poetry groups and workshops for her friends and community members by night. Abby’s most recent work can be found in the magazines Glass Mountain, Poetica, and is forthcoming in Channel.

Aida Bechar

Aida Bechar is a collage artist, illustrator and graphic designer. Based in Tel Aviv, she was born and raised in Istanbul, Turkey. As a classically trained artist with old-school Turkish art education, she uses collage as a means to free her creativity and step out of her boundaries. Her process is informed by the absurd, happy mistakes and her love of typography. Aida has exhibited her work in Tel Aviv, Cologne and in New York. She studied Visual Communications in Bezalel Academy and holds an MFA degree in Illustration from FIT, NYC.

Bruce Black

Bruce Black is editorial director of The Jewish Writing Project. His poetry and personal essays have appeared in numerous publications, including Soul-Lit, The BeZine, Bearings, Super Poetry Highway, Poetica, Lehrhaus, Tiferet, Hevria, Jewthink, The Jewish Literary Journal, and elsewhere. He lives in Highland Park, IL (USA).

Daniel Niv

Daniel Niv majored in Literature and Creative Writing in both Hebrew and English. She works as a professional reader for publishing houses, and is the co-founder and co-editor of Spell Jar Press. She received the Bar Sagi Award for her poetry. You can find her published works in Phantom Kangaroo, Anti-Heroin Chic, Amethyst Review, and elsewhere. She is most fascinated with writing poems that are both confessional and referential, writing fiction, and crafting collage-poems in a room full of candles.

Didi Kfir

Didi Kfir is an illustrator, graphic designer, and pattern maker who graduated from Shenkar College of Design and Art. Born in Israel and currently based in Berlin, they are happy to integrate typography with illustration, applying it across editorial and book illustrations, as well as branding projects. Additionally, she enjoys illustrating through embroidery in their personal endeavors.

Elsa Ers Brosh

Elsa Ers is a contemporary artist who was born in 1982 in Istanbul. After having completed her education in Parsons School of Design in Paris and Sorbonne IV, she went on to work in Istanbul as a fashion and graphics designer. Taking the rich cultural elements of textile design and its significance for the history of female artists as a starting point, she went on to produce paintings and collages deeply intertwined with gender identity and what it means to be human and female in the Middle East. She currently resides in Tel Aviv with her family, where she is nourished by the multiculturalism and the constant chaos while exploring multiple media.

Gabriela Paloa

Gabriela Paloa writes short stories, poetry, memoir and non-fiction. She has been highly commended, short and longlisted by Bridport Prize and Fish for flash fiction and memoir. She is currently writing a long essay/memoir called ‘Island hopping: My life’, which is comprised of memoir, nature writing and images. She is a practicing osteopath and lecturer on the human form and activity in the contemporary moment. She works in her Tel Aviv practice and is a member of Physicians for Human Rights that treat women in Palestinian Villages on an ongoing basis.

Hannah Rosin

Hannah is an American writer from Chicago, IL. She graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and works today as a Creative Director at an advertising agency in the United States. Outside of writing, Hannah is passionate about nature, food, adventures, traveling, and spending time with her friends and family. Although she has written poetry on and off throughout her life, she has never submitted a poem to a publication before. But if there was ever a time to put your feelings on paper — it’s now.

Leeor Margalit

Leeor Margalit is studying linguistics at Tel Aviv University. She enjoys reading, writing, traveling, and photographing her friends.

Lilac Sanders

A creative writer turned international relations student, I aim for ideas that transcend borders, both literal and metaphoric.

Lior Maayan

Lior Maayan, born in Israel, lives with his wife near Tel Aviv. He is a hi-tech entrepreneur with Physics & Math background, an IDF Talpiot program graduate, and holds an MSc from the Technion, and an INSEAD MBA. Lior is a member of the 2022-23 Alma-Metanel Fellowship Program and the JTS Schoken Institute program for the arts. He is a graduate of the first Helicon Arabic-Hebrew poetry program & Makom Leshira Arabic-Hebrew Poetry Translation initiative. A Weizmann Institute Life Verse Poetry Laurate, his work has appeared in numerous publications including Granta, Asymptote, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, Write-Haus, Nanopoetica, Mashiv Haruach, Kol Alarab (Arabic tr.), OtroLunes (Spanish tr.) etc. His book “That Green” (Dr. Shira Stav editor), was published by Afik Publishing House in 2019.

Maayan Agmon

Maayan Agmon writes because then she can breath a bit better, this is how her soul can speak and her mind can clear. She has a B.A. in biology and is currently working on completing her M.A. in education, both from TAU. She is also a teacher at the Eastern Mediterranean International School (EMIS) with students from Israel, Palestine and all over the world.

Marina Grechanik

Marina is an artist, illustrator, and art educator based in Ra’anana, Israel, graduated from an art academy in Belorussia. Sketching is one of Marina’s passions. Everywhere she travels, she takes her sketchbook along with her. But the real essence of urban sketching for her is finding stories in everyday routines and combining sketching with daily tasks like taking care of her children, working, or running errands. “A sketchbook and a simple pen – that is all you need to go on a journey every day. Drawing is seeing, so you just need to open your eyes wider and start to sketch!”

Michelle Chiera

Michelle Chiera is a Chicagoan living in Tel Aviv for eight+ years, hoping to use storytelling as a way to find humor and truth in even the darkest moments we see in ourselves and the world around us.

Mona Haj

Mona Haj is a recent graduate from a Visual Communication department. Her work is personal and expressive, addressing social and political issues. She frequently integrates her own body into her creations, adding a sense of openness and vulnerability to her work. By delving into her emotions, she aims to foster empathy for her subjects. As a Palestinian woman in Israeli society, Mona navigates the complexities of her identity and the ongoing conflicts, which she continually reflects in her art.

Moriya Kaplan

Moriya was born in Ukraine, where she received an art education. She currently works and lives in Israel. Moriya specializes in realism; she draws inspiration from the beauty of simple lines and the idealism of nature. Her passion lies in exploring the depths of the human soul, skillfully capturing its emotions through eloquent body language.

Rick Blumsack

Rick Blumsack is an award-winning Fine Art and Street Photographer based in Jerusalem. His photos are “real” and impromptu, not staged or digitally designed. Rick strives to capture the beauty and feeling of the time and place.

Ronit Holtz

Ronit Joy Holtz (b. 1997, United States) is a painter and an installation artist. She completed a B.F.A in painting at the Savannah College of Art and Design in the spring of 2019. In her emerging years as an artist, Ronit has participated in many exhibitions, been featured in galleries and private collections in over 15 countries and states. She currently resides in Tel Aviv, Israel as a permanent studio artist and atelierista (art teacher). Ronit’s recent studio work is about healing through trauma, loss and grief. In the studio she explores ways to tap back into pain, but to cope with it in creative ways using mixed media and found objects infused with nostalgia and personal sentiment.

Sarina Shohet

Sarina Shohet (she/her) is a Berkeley grad and Jewish professional dedicated to the expression of magic.

Thomas Shore

Thomas is a 28 year old University student living in Tel Aviv.

He enjoys writing and studying languages in his spare time.

Uri Ofer

Uri Ofer is an Israeli artist, poet, singer and musician. Uri lives in Tel Aviv, and since the beginning of the war has served in the “oketz” unit of the IDF as a K-9 trainer.